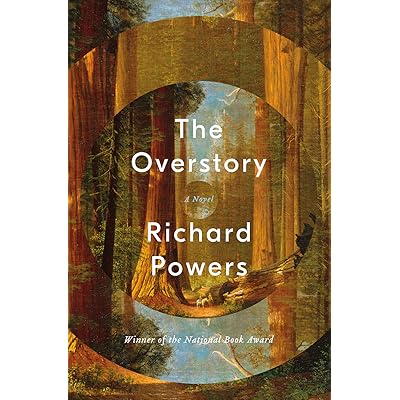

White environmentalism is a thing. I know I’m not the first to say that, but as I read over The Overstory, Richard Powers’ in some ways majestic, and in other ways, deeply problematic 2018 environmental epic of trees, I got a clearer and clearer picture of what white environmentalism is and what some of its problems are. So as a white person with some environmental commitments, I want to explore what I learned here, partly as a review of a book but more importantly, for me anyway, as a way to explore the intersection of whiteness and a certain kind of center-left environmental activism, to see what can be learned about the dangers and limitations of both.

Angela Davis has said that you can’t have meaningful prison reform without working to hear the voices of prisoners. Something similar must also be true about environmental reform: we must listen to the voices of those negatively affected by the system we would deconstruct. And on one level, The Overstory does that, insisting throughout its 503 pages that we listen to the voices of the non-human world: first and foremost, here, this means listening to trees. That works as both a literal and metaphorical engine of meaning through the course of this book. All the lives (animal and plant) in this sprawling multi-generational epic converge in various ways, like the intersecting root systems and crowns of trees (the metaphor is very obvious, but it works in a lot of ways anyhow). Several of the main characters become committed to listening to the messages the arboreal world is conveying. It forms the basis of their activism, sometimes academic, sometimes Edward-Abbey-style ecoterrorist, sometimes dot-com-ish, and sometimes passive NPR-twinged suburban-reclusive.

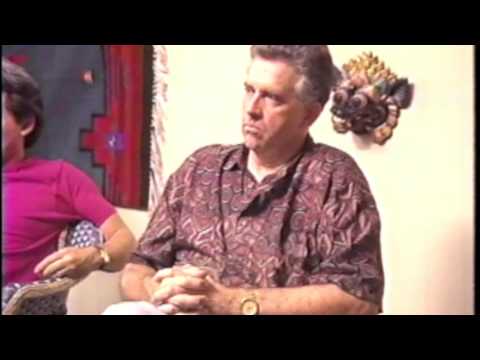

All of that works to de-center what the book many, many times calls the “human” perspective. And that word – “human” – that’s where the problems start for me. If you’ve never seen Lee Mun Wah’s The Color of Fear, I highly recommend it. Near the start, Victor Lewis, a black man, suggests that one of the things white people do the most to perpetuate and expand their own privilege is to insist upon talking about “humanity” in the absence of any consciousness of race. He names this as a particularly effective form of “mystification” that sustains oppression of people of color by refusing even to acknowledge such a term’s legitimacy. “We’re all part of the human race” is a very familiar way to say “I don’t see color” or “I don’t want to talk about race.”

The Overstory embodies this sort of mystification so thoroughly that the race of nearly all of its major characters is not named — they’re obviously white. There are two characters who are established as people of color: Neelay, the son of Indian immigrants who reside in the Bay Area, and Mimi, the daughter of Chinese immigrants who make their home in suburban Chicago. These characters definitely are people of color, but they are clearly people of color conceived of by a white author thoroughly enmeshed in whiteness, and their characters also are very quickly narrated into assimilated, upper-middle class “model minorities.”

Neelay is a multimillionaire game designer phenom – in-game, we read that

“his features take on different racial casts depending on the light and what town he’s in” (375). His ethnicity does arise a few times in dialogue with his parents, who (surprise surprise) are described as the kind of goofy foreigners who insist upon the “old world” traditions (arranged marriage, etc.) that Neelay has no time for.

Of Mimi’s (IRL) character the narrator writes: “Once there was a little girl, bristly, a bully, even, trying to preserve harmony across a great divide. Not yellow, not white, not anything Wheaton had ever seen” (399). Her parents seem to have immigrated as part of the post-war skilled-worker programs that have contributed so mightily to the “East Asians are good at math and science” stereotype. Her father, the arch suburbanite, is obsessed with the American national parks system, cataloging precise dates, times, mileages and weather patterns to plan to precise summer camping adventure, until he eventually is swallowed upon by the kind of emptiness that may lurk at the bottom of that suburban existence, when he kills himself.

Neelay and Mimi are both people of color who are very comfortable for white authors to write, and for white audiences to read about. They are both members of the 1%, or at least the 10%, and if they experience any tensions within white society (probably the real-world versions of them would) we do not read about it. The rest of the cast of characters, as far as I can tell, are white – and so firmly ensconced within white culture that their whiteness need not even be named.

And they are all environmentalists of one stripe or another. They all, to various extents, espouse Sartre’s “Hell is other People,” preferring the company of pine needle scents, glorious visions of shimmering leaves, and so on. They all clearly believe that the problem is that “people,” “humans,” “groups,” are incapable of seeing what they are doing to “the world.”

“we feel that the field is wide open, and each man can stand on his own… “

Back to The Color of Fear: David Christensen, the documentary’s “I’m not racist” white racist guy par excellence at one point becomes exasperated with Victor and the other people of color who are sharing their experiences of restriction and limitation, declaring that “we [white people] feel that the field is wide open.” He (and many other white people, including myself sometimes) insist upon a naive sort of access to “the field,” eschewing the idea of groups and camaraderie of an ethnic or racial variety. Something worth unpacking here is the resonance that David’s vision of his own humanity – “the field is wide open” has with the The Overstory’s characters’ visions of how they prefer to interact with “nature.” They want “the other people” out of the way, they want them to see “the world as it is” and not just “the world as it exists for humans.” And Victor goes on to suggest to David that he is wrong in his framing of his experience:

You are not standing on your own ground; you’re standing on red ground! And that’s what it means to be White: to say that you’re standing on your own when you’re standing on somebody else’s! And then mystify the whole process so it seems like you’re not doing that.

Victor Lewis, The Color of Fear

We can add to this that a great deal of environmental destruction was necessary for the construction of white identity as well. It’s significant that David calls it a “field” and not a “forest.”

Related to this vision of David’s “wide open” field is a strong notion of individuality. In David’s words, “I never considered myself as you do: a part of an ethnic group. I think that’s what you’re looking for and you’re not going to find that among us because we don’t look at ourselves as an ethnic group.” And all the main characters of The Ovrstory view with great suspicion any sort of collective human endeavor. They think of “humans” could only learn to take “nature” on its own terms, things might improve. But they cannot find any way to make this happen, and so each of them, one way or another, fails. They end up in prison, or witness relocation, disguising their identity, or dying by suicide, or as martyrs to spouses they had long since stopped loving. None of them succeeds, as far as I can tell, in moving the scales away from “human”-centered visions of the world into more deeply ecological-consciousness-infused ones.

What positive suggestions there are come from in the form of a kind of Neelay’s latest MMORPG, the narrator’s descriptions of which are banal to the point of frustration, Patricia’s suicide-poisoning in front of a TEDTalk-like audience (her answer to “what is the best thing an individual can do for the planet?”), and Dorothy’s embrace of crazy-old-woman eccentricity, refusing to groom her suburban St Paul lawn and yard.

These three alternatives – roughly, technofuturism, self-immolation and crochety-old lefty – are all predictably and painfully WHITE to their cores.

I’ll now come back to Angela Davis’s idea about prisoners and prison reform. So who are the “prisoners” of environmental collapse? Yes, the trees. Yes, the animals, but also, and this feels really really important, people of color, especially what is sometimes residents of what is sometimes called “the global south,” many of whom are much more likely to be impacted both now and in the future by climate change and other human-caused environmental damage than the average character in The Overstory. And the voices of those billions upon billions of human beings are nearly 100% absent from this text. This is not an overstatement. This book is 503 pages, and the impacts being felt and soon to be felt upon the global south scarcely merit a mention by any of the activist protagonists that form this novel’s cast.

For the most part, the environmentalists in this book see the problem in aesthetic or even recreational terms (though probably they wouldn’t put it that way). Sure, they are concerned about the planet’s ecosystem collapsing, but when it comes down to it, what they’re really scared of losing is the ability to drive out into the country and go camping, or sit in a field and paint pictures of trees, or smell pine needles outside their office window.

A famous ad, often dubbed the “Crying Indian,” first aired on Earth Day, 1970, did a lot to advance the idea many Americans (especially White Americans) hold about Native Americans and “the environment.”

And it’s not true that race is never discussed in The Overstory. One racial identity that does arise several times is that of Native Americans. But when they come up, it is never as discrete individuals, or even as specific groups with specific histories, but always as metaphors for the environment, or sustainability, or communion with nature.

The usual story told about us–or rather, about ‘the Indian’–is one of diminution and death, beginning in untrammeled freedom and communion with the earth and ending on reservations.

This is not a new phenomenon. As David Treuer, in The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee: Native America from 1890 to the Present puts it, “that we even have lives–that Indians have been living in, have been shared by, and in turn have shaped the modern world–is news to most people. The usual story told about us–or rather, about ‘the Indian’–is one of diminution and death, beginning in untrammeled freedom and communion with the earth and ending on reservations.”

Here is every place (to my knowledge) Native Americans are mentioned (or even alluded to) in The Overstory:

- “He [Douglas] doesn’t know how old this city is, but the tree was clearly a sturdy sapling before any white people came near this spot” (206).

- “We [Olivia/Maidenhair, speaking to loggers] have to learn to love this place. We need to become natives” (288)

- Olivia again later on: “We need to stop being visitors here. We need to live where we live, to become indigenous again” (339)

- Mimi in the car with Douglas: “They listen to a book on tape: myths and legends of the first people of the Northwest. The old man of the ancients, Kemuch, springs up from the ashes of the northern lights and makes everything. Coyote and Wishpoosh tear up the landscape in their epic fight. The animals get together to steal fire from Pine Tree. And all the darkness’s spirits shift shapes, as numerous and fluid as leaves” (346).

- Or more broadly, about the indigenous peoples of the world: “She [Patricia] has come across the same stories everywhere she collects seeds–in the Philippines, Xinjiang, New Zealand, East Africa, Sri Lanka. People who, in an instant, sink sudden roots and grow bark… Just upriver, the Achuar–people of the palm tree–sing to their gardens and forests, but secretly, in their heads, so only the souls of the plants can here. Trees are their kin, with hopes, fears, and social codes, and their goal as people has always been to charm and inveigle green things, to win them in symbolic marriage. These are the wedding songs Patricia’s seed bank needs. Such a culture might save the Earth. She can think of little else that can” (394)

That’s it. In every one of these instances, Native Americans are not a concrete reality, not members of the human community, but metaphors, object-lessons, White romanticizations of “the Native” as “the environment.” Truer describes it as “the survivalist fantasy that, every few years or so, sends some white guy off in search of a New World version of Plato’s cave: a retreat from which he engaged with the natural world, often in a self-proclaimed attempt to better understand the human world he left behind,” (339) a vision he says is “markedly different” from the “collective view of survival” he sees as much more authentically enmeshed within his brother Bobby’s experience, and the experience of Indians more generally.

Now what might have been learned had Richard Powers, clearly a gifted writer and committed researcher, had spent the time (and the pages) actually listening to and then writing about the perspectives of people like David Treuer, in our world, who already identify asindigenous? When Olivia (who adopts the pseudo-Native American name “Maidenhair”) says “we” must again become indigenous, who is the “we” she is referring to, and who is it excluding? In her mind, that there are actual, living, breathing human beings who are indigenous, whose might actually be real, non-mythical, and potentially even involved in the struggle she is undertaking– the thought doesn’t even occur to her.

Another group of people barely even mentioned are black Americans. Nick does, on several occasions, think of the refrain to Sam Cooke’s “A Change is Gonna Come,” but that is the only lyric of the song cited. That song is about much more than just “change” as an empty signifier – it is about specific experiences of violence, segregation and injustice endured by black people in the service of whiteness in the United States. But that aspect of the song, of course, is not considered by the character or by the narrator. It’s just “change.”

“The triangular profit making the infant country’s fortune: lumber to the Guinea cost, black bodies to the Indies, sugar and rum back up to New England, with its stately mansions all built of eastern white pine”

At one point, Dorothy does muse about the triangular trade routes and their impact upon the trees: “The triangular profit making the infant country’s fortune: lumber to the Guinea cost, black bodies to the Indies, sugar and rum back up to New England, with its stately mansions all built of eastern white pine” (422). This comes close to exploring the connection between the dehumanization of kidnapping and enslavement, one the one hand, and destruction of trees to create lumber, on the other. I say “close” because nothing whatever comes of it in the context of the book. Rather than include a Black character who might be in a position to speak to it from this perspective, it’s just a passing thought within the minds of a white person.

I get that opinions like the one I’m expressing here can seem frustrating. From one perspective, I’m just saying “this book isn’t about race” and it might feel like that’s just because the author didn’t choose to make it like that, and I shouldn’t expect every book to be about that issue. After all – you might argue – this book isn’t racist, right? In a world dripping with overt racism in the highest positions of power, why castigate someone like Powers, who’s clearly a center-left “good guy,” probably didn’t vote for Trump, etc.?

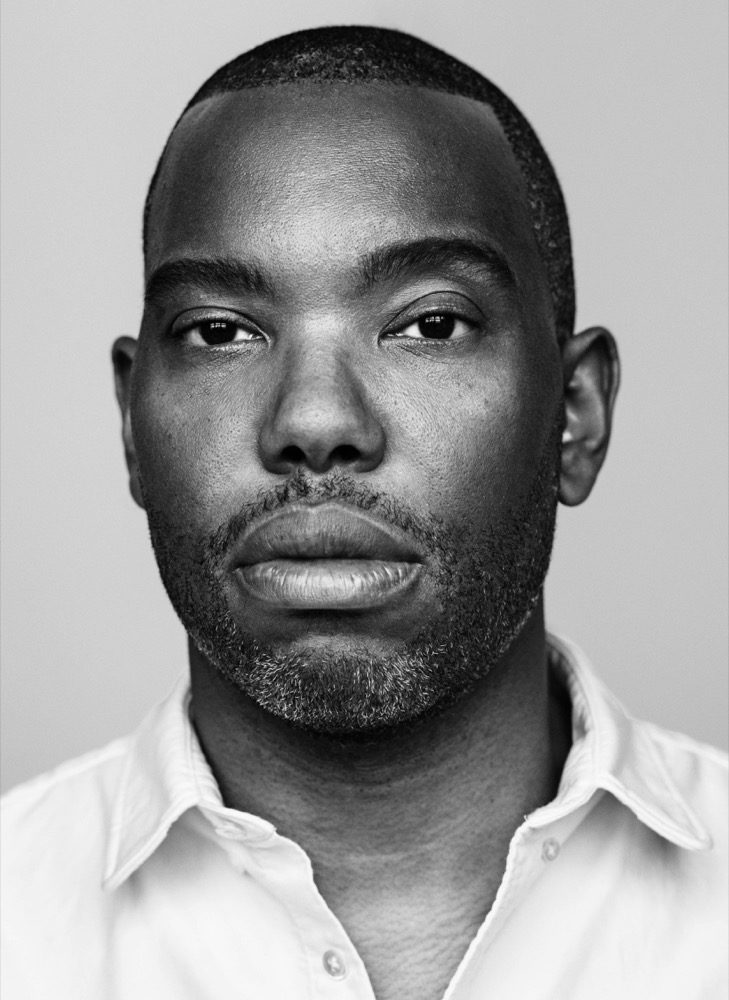

But I think it’s more complicated than that. The way I would put it is that this book – like much of the rest of the center-left, is thoroughly enmeshed within whiteness and shows little self-awareness of that, little willingness to interrogate or even acknowledge that fact. Ta Nehisi Coates’ words are instructive:

The left would much rather have a discussion about class struggles, which might entice the white working masses, instead of about the racist struggles that those same masses have historically been the agents and beneficiaries of. Moreover, to accept that whiteness brought us Donald Trump is to accept whiteness as an existential danger to the country and the world.

Ta-Nehisi Coates, “Donald Trump is the First White President“

And we see that “white working class” in The Overstory too – they’re shown as mindless, unsophisticated toadies for the lumber industry, people who “just don’t get it.” The common ground that the activists and the loggers inhabit as white people remains taken for granted.

And if you think I’m just taking things too seriously — this is a novel after all – I think there’s a deeper significance for this book. This is a novel, yes, but it is purporting to be a novel about politics, environmentalism and activism. It’s not merely meant for entertainment. It takes itself very seriously and has change on its mind. But if we are really going to strive for environmental change, we must be able to reflect on the role race might play within that movement. As Coates points out in the Trump essay, a long string of authors, at least as far back as WEB DuBois, have seen the existential threat posed by white supremacy. That threat extends to the environment as well. I am not saying racism is the root cause of environmental degradation, or that the arguments the book does make entirely miss that point. What I am saying, though, is that we must interrogate racism in the course of examining the causes of environmental destruction. It’s part of the story, and the voices of people of color impacted by that story must be acknowledged and heard. As long as we’re just talking about “humanity” without a consciousness of the role race plays in the construction of that concept, we are bound to replicate the problems that race has brought us. Any social or environmental problem is implicated by it, even if not its sole cause.

There’s a set of moments in the emerging radicality of psychology grad student Adam Appich woven into this book, moments that seem meant to help along members of the academic-industrial complex as they see the role they might play in helping to solve the environmental crisis. In one of them, as Adam begins to undergone this change, we read that “he tries to read a novel, something about privileged people having trouble getting along with each other in exotic locations” (331-332). This is intended as parody of how superficial fiction can see in the face of an activist who is actually willing to put his life on the line. What I do not think the author of this passage may have realized is just how much it is, in fact, a description of The Overstory itself. Race privilege left unexamined in this book means that ultimately, its conclusions double back on themselves: the forests just become so many “exotic locations” where “privileged people have trouble getting along.” Less is learned than it seems.

When Patricia opines that “the world had six trillion trees, when people showed up. Half remain. Half again more will disappear, in a hundred years” (432, my emphasis), what she might better have said was “white people.” Because the people who made themselves white destroyed the vast majority of those trees, and that they did so, and that they made themselves white, are connected in time. I’m not saying whiteness caused that, but I am saying we need to investigate that relationship. The Overstory does not do that, and it’s a problem.

The specter of 9/11 haunts the book’s latter pages. Dorothy, watching TV, hears a newscaster speak: ‘That is the second tower. That just happened. Live. On our screen… It’s deliberate,’ the screen says. This must be deliberate'” (397). “This must have been deliberate” I think is intended to heighten the contrast between the clearly human-caused disaster of 9/11 that we can recognize and the ticking time-bomb of environmental collapse that we cannot. Somewhere else it brought me, though, is the words of Gyasi Ross:

It [9/11]was undoubtedly a tragedy. But September 11th wasn’t a surprise, at least not for Native people and many people of color. No, Native people were already well aware of how destructive and evil people could be. How did we know? AMERICA TAUGHT US THAT; really, September 11th was only a surprise for white people and for those who didn’t realize that America had already perpetrated many September 11ths of its own. Native people knew that. We knew that America had a whole bunch of blood on its hands and that there was always a harvest season, always a reckoning. Sir Isaac Newton gave that harvest a name in his Third Law of Motion, that every action has an equal and opposite reaction.

Gyasi Ross, The Day White Innocence Died: An Indigenous Take on #September11:

To deploy The Overstory’s foundational metaphor, There are arboreal connections between the anti-human destruction of 9/11, the attempted genocide against Native American peoples, the kidnapping and enslavement of black people, and the oppression of so many other groups of people of color that do not even merit mention in The Overstory, connections that run right through European peoples’ construction of their own whiteness. But before we can see them, we must at least name them and learn about them from perspectives more multiple than the terms of Richard Powers’ novel allow.