[This is part 5 of a longer series – previous track – “Re:Definition” – next track – “Brown-Skinned Lady”]

The opening four tracks of Mos Def and Talib Kweli are Black Star feel like they form a kind of opening act. The fifth song on the album, “Children’s Story,” a cover (sort of) of Slick Rick’s song of the same name, marks the album’s first real break in the action. We feel the beat slow down and a less intense vibe takes over, starting with a skit. “Uncle Mos” is trying to put two children to bed. Those children are recounting stories of gangsters fighting in the street (a big part of the subtext of the last track, “Re:Definition”), and Mos is like “enough with all that” – the kids demand a story, and he delivers ones. What follows is an intricately ironic performance. It’s a retelling of Slick Rick’s own “Children’s Story,” but very cleverly reworked. To add to that, the new story becomes also a story about reworking songs – about the difference between creatively evolving a song, and un-cleverly commercially imitating it. The song itself very conspicuously steals Slick Rick’s beats to deliver a morality tale about stealing beats.

Academic excursus: “Intelligent embellishment…From Flatbush settlement”

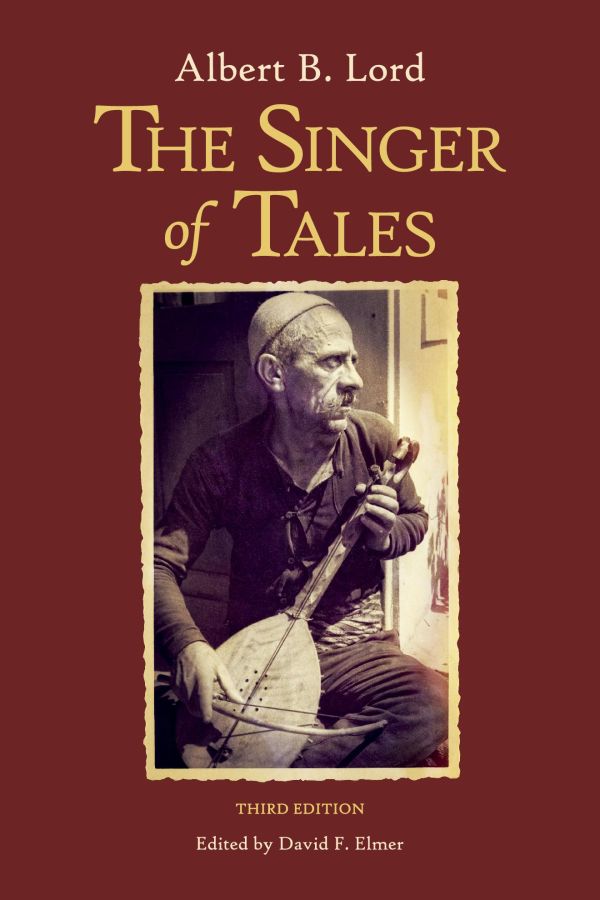

The Singer of Tales (1960) is a fascinating book by Alfred Lord. In Classical Latin and Greek studies circles (hear me out), it’s a pretty famous piece of the answer to the age-old Homeric Question – who was Homer? Related questions: was he a single person or a group? Did he write his poetry down? Was he blind? Was he a he? The Singer of Tales is a popularization of some of the more academic work done by Milman Perry in his very scholarly The Making of Homeric Verse. Perry argues that the key to understanding The Iliad and The Odyssey is to read them as collective oral compositions created by many generations of illiterate bards – singers of tales.

Alfred Lord writes about visiting a community of Serbian bards in the 1930’s – they can’t read or write, but they can rattle off epic poems hundreds of lines at a time, and imitate and play on each others’ epics in ways that amaze Lord. He reports asking a group who’s the best “singer of tales” – they all agree, it’s this one guy. He then asks another guy (not the consensus best guy) to perform a song – he does. It’s about someone riding off to battle on their horse or something. He turns to the best-guy and says “can you do that?” The best-guy nods yes – Lord looks back at the rest of the group and they all seem unsurprised by the answer, all nodding along. “Will it be better?” Again, everyone nods. The next day, Lord comes back, and the best-guy performs his version – it includes something like 95% of the lines of the original, but is expanded five-fold too (he proves this by recording and analyzing it later). Lord is just amazed that this is possible, especially considering the first guy only performed it once, and the best-guy didn’t take any notes or anything. This and other stories like it form the core of his argument – that the Iliad and the Odyssey are transcribed oral performances, not literary (i.e. written) compositions. The conclusion is this: human beings can do this, and have been able to for thousands of years, long before the phenomenon of widespread writing or literacy. And they don’t need to be cultural elites – in fact it’s better when they’re not. Lord and Perry’s bards were farmers who work all day before performing for each other; their hypothesis is that the “Homeric” bards were just the same.

In Mos Def’s words from Re:Definition, “intelligent embellishment… from Flatbush settlement” – oral composition from working class communities – is a core method to creative, democratic art that hip hop at its best can be. Taking someone else’s story and using your cleverness and wit to make it better yields a uniquely satisfying sort of listening experience – freestyling in a streetcorner or public park cypher becomes part of a tradition that stretches all the way back to the pre-history of humankind, whether in Asia, Africa or Europe.

Two “Children’s Stories”

In a way, Mos Def and Talib Kweli’s “Children’s Story“ plays the same game with Slick Rick that that best bard was playing with the other lesser one. The story follows all the same cadences and rhythms, and tells a similar story: about young kids caught up in “the American Dream.” Slick Rick’s is a morality tale, about what happens to kids who slip up and start stealing, and otherwise go in for that gang life. Mos Def’s tale is a cleverly overlaid chronicle of two kids who begin to steal beats (i.e, sample, to make hip hop) and make it big with cross-over pop hits. Not entirely different, at all, from Mos Def and Talib Kweli themselves and what they’re doing to Slick Rick’s beats.

So another student, Avery – earnest, hard-working math and science student, white – he and I are talking about his analysis of this song and says to me that it’s sort of weird that they tell a whole story about people stealing beats, and they stole this beat, and a lot of the words, from Slick Rick. They’re lecturing these kids about what not to do, and they’re doing it. Avery offers this as a criticism. Like a lot of other white kids I’ve done this work with (and like myself when I don’t reflect) he misses the irony. He does not experience this as a medium – or performers – who could exhibit that level of cleverness. Everything has to be an obvious lesson, usually about “racism and how bad it is,” and if it’s not that, they’re likely to see it as just crude bravado or party music. I look at him and just ask “don’t you think they probably realized that irony?” He’s like “I never thought of it like that.” But, truth be told, I really hadn’t until he and I had that little convo. Here’s where I got when I set to thinking about it:

This is where the album most directly confronts that cultural appropriation/cultural appreciation duality that the album’s intro alluded to. The performer being described in the song is a sort of accomplice to pop-radio appropriation of his talents; in telling that story, Mos Def and Talib Kweli is engaged in an act of cultural appreciation, an homage Slick Rick. Another bit of classics knowledge feels relevant – Roman poets made a distinction between imitatio and emulatio (imitation and emulation). Imitatio means ripping someone off and trying to claim credit – that’s what the would-be hip-hop performer in this song is doing. Emulatio means taking someone else’s work and showing them up, through parody, embellishment, etc. What Lord’s best-guy did. What Jay-Z is talking about when he disses Nas by boasting “So yeah, I sampled your voice, you was using it wrong” And also what Mos Def is doing to Slick Rick here. They’re critiquing imitation through the deployment of emulation – i.e., “intelligent embellishment.” Avery didn’t know this distinction and presumably neither do Mos’s fictional nephews. So the song sets out to teach them. And where Slick Rick’s is a tale of good kids turned bad to a life of crime, Mos Def’s obliquely draws the connection between imitation and violent crime, capitalism and white supremacy, on the one hand, and then emulation, creativity and Black liberation, on the other. But the kids don’t get it and call him a hater.

Let me break down the song in more detail:

Fade in two two grown men pretending it be children, telling stories about a neighborhood gunfight. Then a real grown up agrees to tell them a story- which right away sounds like Slick Rick’s story of the same name.

Look at Slick Rick’s own opening:

Once upon a time not long ago

When people wore pajamas and lived life slow

When laws were stern and justice stood

And people were behavin’ like they ought ta good

There lived a lil’ boy who was misled

By anotha lil’ boy and this is what he said

“Me and Ty, we gonna make sum cash

Robbin’ old folks and makin’ the dash”

Look how Mos Def changes it, in bold, to emphasize old-school hip-culture:

Once upon a time not long ago

When people wore Adidas and lived life slow

When laws were stern and justice stood

And people was behaving like hip-hop was good

There lived a little boy who was misled

By a little Sha-tan and this is what he said

“Me and you kid we gonna make some cash

Jacking old beats and making the dash”

Now it’s a morality tale not about gangster life, but a precisely parallel tale about someone seduced by the dream of making bad hip hop for prophet – “working round the clock for pop radio,” his associate, a “sista who couldn’t sing for sh*** but the mix will assist her,” before he runs into Mos Def, who does his best to dissuade him from this line of work (we could read this song itself as that attempt at dissuasion).

Look at how the criminal behavior described changes too – here’s Slick Rick’s version

they did the job, money came with ease

But one couldn’t stop, it’s like he had a disease

He robbed another and another and a sister and her brother (stick ’em up, stick ’em up)

Tried to rob a man who was a D.T. undercover

And again Mos Def’s new version:

They jacked the beats, money came with ease

But son, he couldn’t stop, it’s like he had a disease

He jacked another and another — Michael Jackson, Stevie Wonder

Set some R&B over the track for “Deep Cover” (187!)

Instead of robbing people in his own community of their actual possessions, he’s taking from his musical heritage to make mediocre music for mass consumption.

Cleverly riffing on the fact that a “45” is both a record and a gun, Mos Def tries to get him to transition from corporate to conscious rap. Which in a way continues the project of Re:Definition, just in a more humorous and light hearted way. He fails and the kid, “so close to glory,” is killed.

Here’s the concluding moral – again, Slick Rick’s version first – about a kid caught up in violence of street life:

He was only seventeen, in a madman’s dream

The cops shot the kid, I still hear him scream

This ain’t funny so don’t ya dare laugh

Just another case ’bout the wrong path

Straight ‘n narrow or yo’ soul gets castGood night!

Again, look how Mos Def Changes it into a cautionary tale about the United States, music industry and capitalism, again, interjecting a crucial hip-hop allusion:

He was out chasin’ C.R.E.A.M. and the American dream

Tryin’ to pretend the ends justify the means

This ain’t funny so don’t you dare laugh

It’s just what comes to pass when you sell your ass

Life is more than what your hands can graspGood night!

Which brings me back to Avery – to give him full credit, he recognized the depth of “tryin’ to pretend the ends justify the means”- just hadn’t quite put 2 and 2 together and explored how the song’s whole allusive context develops the parallel between gang violence and the corporate music industry. And again, what I think this album does best is call people in. Was I frustrated that Avery didn’t “get” the irony initially? Sure. Did it confirm my sense of how common white blindness in the face of Black Creativity? Sure. But then, I’ve been there- I’ve missed the irony, assumed I got something and that it was simplistic, rather than that it as complex and I wasn’t there yet, and somehow this song reminds me of that in a way that asks me to call Avery in, rather than shame him for not being “woke” enough.

Uncle Mos’s fictional nephews also miss the point: “yo what is he talkin’ about? I don’t know – life is more than what your hands can grasp? I don’t know what he means. He’s just a player hater.” But he loves them – they’re his nephews.

[This is part 5 of a longer series – previous track – “Re:Definition” – next track – “Brown-Skinned Lady”]

6 thoughts on ““Children’s Story” (Track 5)”