[This is part 11 of a longer series – previous track – “Yo Yeah” – next track – “Thieves in the Night”]

This song is massive and complex – there’s no way around that – but it’s also catchy and engaging. I fear my analysis of it below doesn’t live up to that, but really good music just outstrips our abilities to explain it. I’ve tried my best. The album’s final three tracks, to me, work like 3 movements in a conclusive hip-hop symphony.

I’ll start more concretely: I am remembering a recording made by another student – Sophia1 – she identifies as Latina, and speaks English and Spanish. There was something awesome about her finding this track in the darkest, loneliest days of the pandemic, in early, pre-vaccine 2021 , 11 tracks in to this album, and hearing its Spanish interlude, feeling seen by it, and in turn appreciating it:

Escuchela, respirando como yo

Ojos sinceros, escondiendo pena y temor

El silencio de mentira, tocando al hogar

Escapando sentimientos entre ella y yo

Which Google translates to:

Listen to her, breathing like me

Sincere eyes, hiding sorrow and fear

The lying silence, touching the home

Escaping feelings between her and me

In the opening moments of her recording, Sophia’s voice brightened when she just said simply “and the Spanish!” And was a good reminder to me of the simple truth that music works in different ways for different people.

This passage acts as a chorus, though a part of it it precedes the song. But before that there is another interlude, excerpted from an 80’s documentary called Style Wars – actually available in its entirety (I think):

We hear a graffiti artist saying:

“What’d you do last night?”

“We did, umm, two whole cars

It was me, Dez, and Mean Three, right?

And on the first car, in small letters, it said ‘All you see is’

And then, you know, big, big, you know, some block silver letters

That said ‘crime in the city’, right?”

“It just took up the whole car?”

“Yeah, yeah, it was a whole car and shit…”

This brings to mind another student – Olivia – white – who made one of those irony-missing readings of this situation like I also described with Children’s Story: on her recording, she explained that this clip highlights the “sad reality” that so many people living in “these neighborhoods” are “unfortunately forced into a life of crime.” This is, to me anyway, a very recognizable and common variant on what Ibram X Kendi calls “assimilationist” racism – which Kendi summarizes as “based on the assumption there is something wrong with another racial group that needs changing.” Though it is often seen as a “milder” form of racism, or even embraced by white liberals and sometimes Barack Obama, Kendi argues that it does as much, if not more damage, than the more traditional “segregationist racism.” Here the assimilationism comes up in the idea that people in “these neighborhoods…turn to crime,” as though something breaks inside them and their psychologies are somehow compromised (and could therefore perhaps be “fixed” by white saviors). Olivia doesn’t blame the people directly, more “these neighborhoods” (even though it is not at all clear which neighborhoods, really) – this view places a seemingly liberal take on it by suggesting that the circumstances are to blame. That the circumstances make some people failures, which is “unfortunate.”

Before I’m too hard on that reading, I can fully acknowledge that there was a time and place I would have said what she has said, and would have even though that what I was saying was somehow enlightened or compassionate. That is one of the reasons White liberalism can be so dangerous.

To me now though, this clip means something entirely different: these graffiti artists are calling attention to the irony of their art being labelled as criminal, and the way it contributes to the overall representation of crime in urban spaces – really they are calling attention to the white liberal representation AS a representation, one that sees “these neighborhoods” as irredeemable at some level. The artist is commenting on this by graffiti-ing “all you see is – crime in the city.” There are layers of irony here the artist has cleverly invoked. All “YOU” see – when “YOU” look – at which I feel mildly called out, like it’s asking me, or Olivia, or any else who’s been subject to these representations: when you look at the city, what do you see? How is your vision impacted by preexisting negative representations of what you are looking at, representations the culture has conditioned in you? Of course it does that in fewer words and without the roundabout explanation. Which make it art and makes this awkward prose.

The following personification of the city – “Escúchela, la ciudad respirando” -“listen, the city breathing” strikes out against the white-liberal vision of the city – it’s not a space of death, but life. And the fact that it’s in Spanish, when the opening vignette is in English, accentuates the distance between the two ways cities are seen – and the impacts those perceptions have on urban policy-making, a topic that looms over the song’s verses. A genius.com annotator suggests that the chorus’s whispered tone is important too – it’s like, to an external observer, the true life of the city is not so easy to hear, especially when “all you see is crime in the city.”

Each of the song’s three verses is a complex thicket of lyrical clusters. We get one verse each from Mos Def, Talib Kweli and then finally a feature verse from Common, crucially expanding the album-long metaphorical freestyle cypher to Chicago. Rapping in 1998, Common laments the coming gentrification of the Cabrini Green housing projects (which were, in fact, destroyed in 2000)- listening back now, in 2024, that lament takes on a retrospective dimension, in a way compounding the tragedy.

These verses are just huge, crammed full of theoretical constructs, pop-culture references and personal story – here’s what Mos Def puts down:

The new moon rode high in the crown of the metropolis

Shinin’, like “Who on top of this?”

People was tusslin’, arguin’ and bustlin’

Gangstas of Gotham hardcore hustlin’

I’m wrestlin’ with words and ideas

My ears is pricked, seekin’ what will transmit

The scribes can apply the transcript

Yo! This ain’t no time where the usual is suitable

Tonight alive, let’s describe the inscrutable

The indisputable (What!)

We New York, the narcotics, draped in metal and fiber optics

Where mercenaries is paid to trade hot stock tips for profits

Thirsty criminals sic pockets

Hard knuckles on the second hands of working-class watches

Skyscrapers is colossus, the cost of livin’ is preposterous

Stay alive? You pay or die, no options

No Batman and Robin

Can’t tell between the cops and the robbers

They both partners, they all heartless, with no conscience

Back streets stay darkened

While unbeliever hearts stay hardened

My eagle talons stay sharpened, like city lights stay throbbin’

You either make your way or stay sobbin’

The shiny Apple is bruised but sweet, and if you choose to eat

You could lose your teeth, many crews retreat

Nightly news repeat who got shot down and locked down

Spotlight the savages, NASDAQ averages

My narrative grows to explain this existence

Amidst the harbor lights which remain in the distance

The verse begins situating Mos Def as a resident in the city, as “the new moon rode high in the crown of the metropolis.” A new moon is also a “curious celestial phenomenon,” kind of like a “black star.” It’s a paradoxical, contradictory image – in spite of its name, a “new moon” cannot be seen, just like a “black star.” This foreshadows the contradictions inherent in a seemingly simple notion like “crime” – this is a verse about the crime you can’t see because you don’t see it as “crime.” He begins talking about “gangsters of Gotham hard core hustling.” And again, if “all you see is crime in the city,” you are likely to hear that as a reference to stereotyped “bleak realities of urban life.” But as the verse evolves it seems much more that those “gangsters” are actually Wall Street tycoons and real estate developers. The same gentrifiers Common raps about in the 3rd verse with “out of the city they want us gone.”

And so Mos Def sets out to bring this to light – in his own words, “to describe the inscrutable” – to articulate the crimes that become normalized- behind the representation of the city that foregrounds graffiti as “crime,” rather than, say, insider trading and racist housing policy decisions. He makes a really interesting statement of methodology along the way: “I’m wrestlin’ with words and ideas/My ears is pricked, seekin’ what will transmit/The scribes can apply the transcript”: he intends to listen to the city, and use the resources of oral composition to transmit and focus its energy, and he will leave it others to document it in writing. This recalls the aesthetic preference for oral transmission – and its political implications- earlier theorized about in “Definition.”

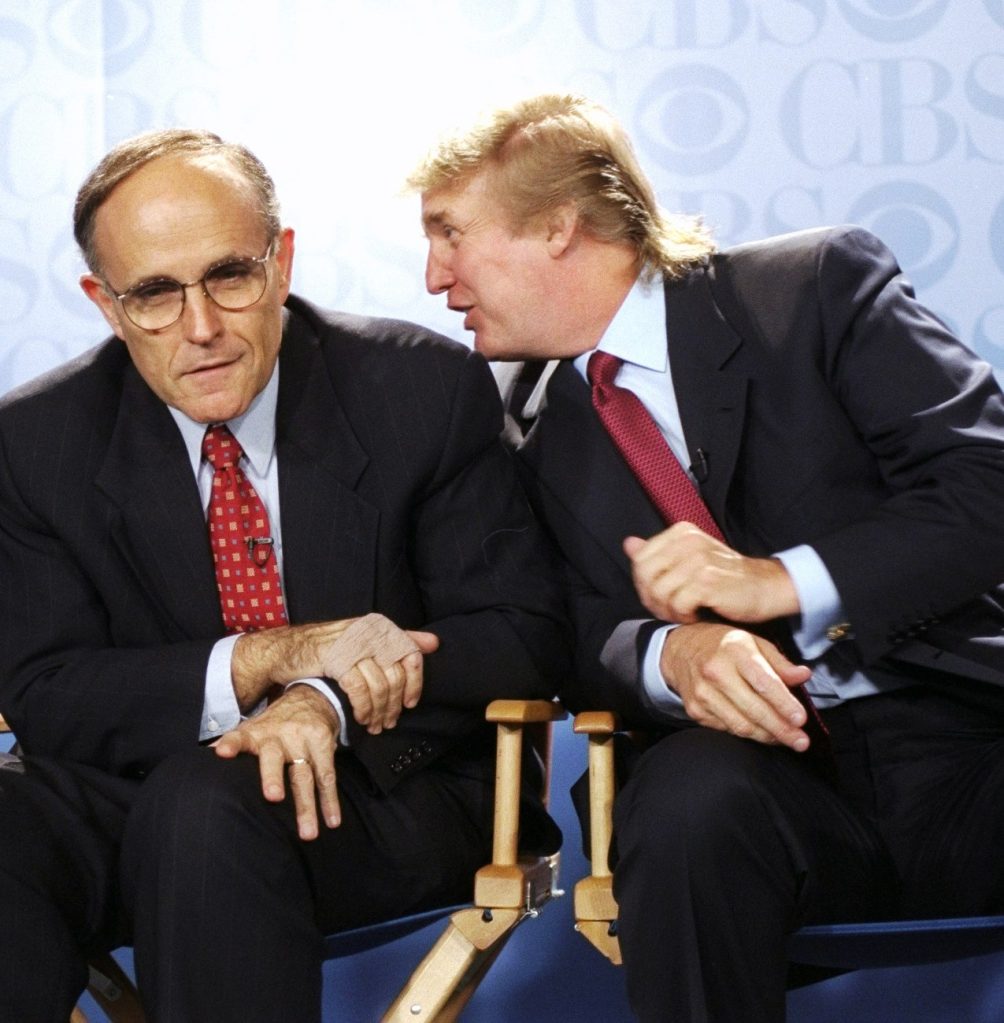

We get a lot more about the true criminal culprits – “spotlight the savages/NASDAQ averages.” The crime is not the easily spotted vandalism of graffiti but instead the development of capital born out of the commodification of labor. And the private security force – the NYPD – that allows this to continue – “Can’t tell between the cops and the robbers/They both partners, they all heartless, with no conscience.” These, in fact, are the real merchants of death in 90’s New York – something Mos Def will later confirm by naming one of them in the album’s closing moments on “Twice Inna Lifetime”- here’s a photo from the era:

Mos Def finishes the verse with another reflective moment – one of my favorite lines on the album actually – “my narrative grows to explain this existence.” He’s theorizing about the purposes hip-hop storytelling can serve against the racist power of capital and the police. And that rhyme pairs with another: “amidst the harbor lights which remain in the distance,” which arguably invokes the famous conclusion of The Great Gatsby – and the green light wherein Gatsby’s capitalistic and erotic urges are joined. Mos Def finishes the verse by setting himself firmly in opposition to the forces of death – his narrative becomes part of the city’s breathing, because “the shiny Apple is bruised but sweet.”

The chorus follows, reinforcing the personification of the city:

So much on my mind that I can’t recline

Blastin’ holes in the night ’til she bled sunshine

Breathe in — inhale vapors from bright stars that shine

Breathe out — weed smoke retrace the skyline

Heard the bass ride out like an ancient mating call

I can’t take it, y’all! I can feel the city breathin’

Chest heavin’, against the flesh of the evenin’

The sigh before we die like the last train leavin’

Confessing their inability to fully articulate their reality (“so much on my mind that I can’t recline”), it’s straightforwardly evocative imagery – important though that “like the last train leavin'” ties into the idea of “the Black Star Line” – half Marcus Garvey separatism and half New York City subway.

Then we get an equally massive and theoretical Talib Kweli verse:

Breathin’ in deep city breaths, sittin’ on shitty steps

We stoop to new lows, Hell froze the night the city slept

The Beast crept through concrete jungles

Communicatin’ with one another and ghetto birds

Where waters fall from the hydrants to the gutters

The Beast walk the beats, but the beats we be makin’

You on the wrong side of the track, lookin’ visibly shaken

Takin’ them plungers, plungin’ to death that’s painted by the numbers

With Krylon applied pressure

Cats is playin’ God, but havin’ children by a lesser baby mother

But fuck it! We played against each other like puppets

Swearin’ you got pull

When the only pull you got is the wool over your eyes

Gettin’ knowledge in jail like a blessin’ in disguise

Look in the skies for God, what you see besides the smog

Is broken dreams flyin’ away on the wings of the obscene

Thoughts that people put in the air

Places where you could get murdered over a glare

But everythin’ is fair

It’s a paradox we call reality

So keepin’ it real will make you a casualty of abnormal normality

Killers Born Naturally like Mickey and Mallory

Not knowin’ the ways will get you capped like an NBA salary

Some cats be emceein’ to illustrate what we be seein’

Hard to be a spiritual being when shit is shakin’ what you believe in

For trees to grow in Brooklyn, seeds need to be planted

I’m askin’ if y’all feel me, and the crowd left me stranded

My blood pressure boiled and rose

‘Cause New York niggas actin’ spoiled at shows

To the winners, the spoils go

I take the L, transfer to the 2, head to the gates

New York life type trife, the Roman Empire state

Mos Def’s verse convicts Wall Street of “inscrutable” crimes; Talib Kweli speaks much on the lower-income Black communities, and expresses a common preoccupation of his (which calls back to Re:Definition) – that internalized racism inhibits the genuine freedom of his fellow Black New Yorkers. Punning on “shitty/city” steps and perches in front of brownstones, he decries how “we stoop to new lows.”

Some clever alliteration, assonance and anadiplosis draws a contrast between law-enforcement violence (“the beast walk the beats” and the liberatory power of street music (“but the Beats we be makin’”). After decrying some kind of messy aspects of street life he seems to free himself from the idea that it’s somehow their fault – “But fuck it! We played against each other like puppets.”

A line I had never noticed here until a student (Oaken – white male really into hip-hop and philosophy) pointed it out to me:

Look in the skies for God, what you see besides the smog

Is broken dreams flyin’ away on the wings of the obscene

Oaken stayed after class one day to tell me about these lines. He made these gestures with his hands like “do you see how many things he’s saying at once there?” He expressed a kind of frustration but also enjoyment in the fact that he could not articulate his interpretation. All he could do, like Jack Black’s character from High Fidelity is to say “it’s so good!” I did my best to tell him I understood the feeling of being pleasantly overwhelmed by lyrical cleverness joined with theorizing.

And Kweli himself articulates his own kind of inability to persuasive, cleverly weaving together his own literary education with that sense that his demands, however coherent to him, are going unheeded:

For trees to grow in Brooklyn, seeds need to be planted

I’m askin’ if y’all feel me, and the crowd left me stranded

As the verse ends he returns to the subway system from the movie clip and chorus, also invoking the world-historical significance of the inequalities, leaning into Roman history, Nas and Billy Joel all at once:

I take the L, transfer to the 2, head to the gates

New York life type trife, the Roman Empire state

After the chorus (this time including Common), and then the Spanish passage I started this post with, Common’s verse notably expands the cypher, speaking on his home-town, Chicago.

Where Mos Def and Kweli’s verses are theoretical, Common’s is much more narrative:

Yo, on The Amen corner I stood, lookin’ at my former hood

Felt the spirit in the wind, knew my friend was gone for good

Threw dirt on the casket, the hurt, I couldn’t mask it

Mixin’ down emotions, struggle I hadn’t mastered

I choreograph seven steps to Heaven

In Hell, waitin’ to exhale and make the bread leaven

Veteran of a cold war; it’s Chica-I-go for

What I know or what’s known

So some days I take the bus home, just to touch home

From the crib, I spend months gone

Sat by the window with a clutched dome

Listenin’ to shorties cuss long

Young girls with weak minds but they butt strong

Tried to call or at least beep the Lord but didn’t have a touch-tone

It’s a dog-eat-dog world, you gotta mush on

Some of this land I must own

Outta the city, they want us gone

Tearin’ down the ‘jects, creatin’ plush homes

My circumstance is between Cabrini and Love Jones

Surrounded by hate, yet I love home

Asked my guy how he thought travelin’ the world sound

Found it hard to imagine he hadn’t been past Downtown

It’s deep, I heard the city breathe in its sleep

Of reality I touch, but for me it’s hard to keep

Deep, I heard my man breathe in his sleep

Of reality I touch, but for me it’s hard to keep

Starting with a shout-out to James Baldwin, Common works with the personification of the city the song began with, making this story work at two levels: is he narrating about the story of a friend who has passed? Or is he speaking of the passing of his city neighborhoods through gentrification? Or both?

Threw dirt on the casket, the hurt, I couldn’t mask it

Is a simple declaration of heartache that works on both levels – the dirt on a literal casket, or the upheaval of terrain that begins gentifying acts of demolition. The very down-to-earth detail of riding the bus just to look at the city, and then the reflection later on about what it means that

Asked my guy how he thought travelin’ the world sound

Found it hard to imagine he hadn’t been past Downtown

Common unpacks the urban renewal he sees before him – which James Baldwin very memorably names as “Negro removal” in this epic interview:

Common invokes a dialectic of neo-indigeneity and gentrification, returning to the idea of love for a his city that seems to be dying:

Some of this land I must own

Outta the city, they want us gone

Tearin’ down the ‘jects, creatin’ plush homes

My circumstance is between Cabrini and Love Jones

Surrounded by hate, yet I love home

When Common wrote this in 1998, Cabrini Green was just beginning to be destroyed; today, you can find a sleek looking Target and some glass-dominated luxury residences. Many of the developers exercised their buy-out clauses, to avoid actually constructing much of the low-rise “affordable housing” the city had promised.

The left is what things looked like around the time Common wrote this verse; the right is more recent. Here’s an account of how that all went down, granted, not nearly as succinct as Common’s words: “outta the city, they want us gone.” When he follows with “Surrounded by hate, yet I love home,” he also, just as succinctly, rebuts Olivia’s perception of this neighborhood, and reminds us that how you feel about that space probably dictates how you feel about the gentrification that follows. Racist ideas have consequences. It is a widely known fact that Chicago never truly replaced the housing it destroyed in the late 90’s and early 2000’s, whatever claims to the contrary it made at the level of PR.

The song ends with the chorus – and its final line – “kiss their eyes goodbye I’m on the last train leavin’” – that is, the Black Star Line. As sociologically and economically deep as this song is, things get even more esoteric and abstract in the following track, “Thieves in the Night,” a song that marks the critical-emotional climax of the album.

- all student names are changed ↩︎

[This is part 11 of a longer series – previous track – “Yo Yeah” – next track – “Thieves in the Night”]

2 thoughts on “Respiration (Track 11)”